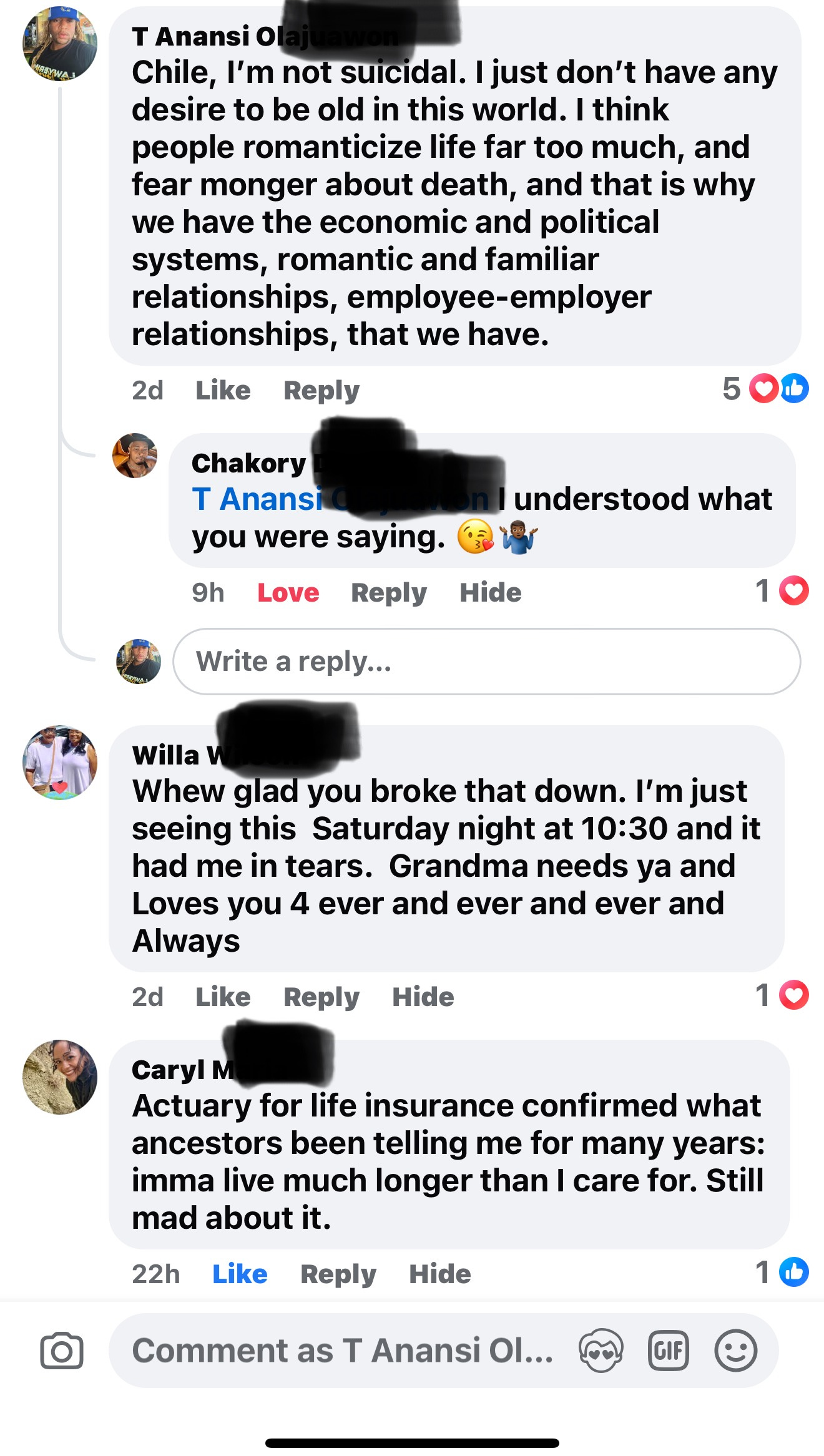

The Facebook status above is an excerpt of response to a question a friend asked my fiancé and I, the night prior, at a bar while we were out on a date. He asked “How long do ya’ll wanna live?” I surprised myself by how quickly I answered the question. There was little hedging, consideration or thought. I was not surprised that I had an answer, rather, that I offered my truth so quickly and inconspicuously. You see, generally, when I tell people, “I am ready to go *in Empress Janet Damita Jo Jackson’s voice* anytime, anyplace” they disassemble and disintegrate into a rambling shadow of themselves, speaking so quickly, as to call to mind Missy Elliot’s lyrical feat in “Work It.”

It is as if, in the old ways of the Black Church—particularly those with connections to Ifa, Hoodoo, Vodoun, namely the Church of God in Christ, Holiness, and Pentecostal folks—they are attempting to simultaneously rebuke a demon coming to “steal, kill and destroy” my life and resolve for living while also speaking life into me because, as the scripture goes “Death and life are in the power of the tongue: and they that love it shall eat the fruit thereof.” I hate to see folks lurching about—spiritually, intellectually, emotionally and, most disturbingly, physically—on my behalf; so generally, I offer a more tempered response of “when the Lord calls me home.” Of course, that is a lie and there is something particularly Churchy about enveloping a lie in the cloth of saintly servitude and obedience that at once is freeingly familiar and hypocritically haunting. I want to tell the truth, dear reader—as I advised you all in my first note here—and I want to tell it beautifully. The facebook status above does and did that—to the degree I felt I could weather the swarm of calls, texts, comments and replies from my mother, grandmother, others and strangers—and I offer the exchange as I thought exercise.

Before I do though, I want to be clear. I’ve never thought of suicide—in the vein of self harm—as something that was a route for me. I’m quite incapable of inflicting intentional physical harm upon myself—save the excess hookah or bourbon—that isn’t merely secondary to the principle of pleasure (again, cue Mother Janet).

Perhaps, this is the Church of God in Christ in me? Perhaps it is a reemerging conviction that indeed, “this world is not my home, I’m just a stranger passing through.” Or, perhaps, more fitting, it is the unwavering call of the question first posited by the Clark Sisters “Is My Living In Vain?” See the lyrics and the fantastic, classic, soul stirring performance below:

Is my living in vain?

Is my giving in vain?

Is my praying in vain?

Is my fasting in vain?Am I wasting my time?

Can the clock be rewind?

Have I let my light shine?

Have I made ninety-nine?No, of course not

It's not all in vain

No, no Lord, no

'Cause up the road is eternal gainIs my praying in vain?

Is my labor in vain?

Is my singing in vain?

Is my speaking, is it in vain?Is my playing the organ in vain?

Is my praying in vain?

Is my, is my, is my labor in vain?

Is my singing, singing, singing, in vain?No, of course not

No, of course not

No, of course notNo, no, no, no, no, no

Of course not

No, no, no, no, no, no

Of course notIt's not all in vain

Up the road is eternal gainIs my praying in vain?

Is my, is my, is my labor in vain?

Is my singing, singing in vain?

I know I'm speaking in vainIs my playin' this organ in vain, at the temple

At the cathedral, at all these churches?

Is my praying, my praying, my praying, in vain? OohIs it in vain? Is it in vain?

Is it in vain? Is it in vain?

No it ain't in vain

No, no, no, no, no, no, no, noNo, no, of course not

No, no, no, no, no, no

No, no, no, no, no, no

Of course notNo, no, no, no, no, no

Of course not

No, no, no, no, no, no

Of course notIt's not all in vain

It's not all in vain

It's not all in vain

It's not all in vain

It's not all in vain

'Cause up the road is eternal gain

I ask the questions addressed in these lyrics multiple times throughout the day. Contrary to your immediate assumptions, beloved, that is not an expression of resignation but instead a daily evaluation of my own humanity, a soul check if you will, a moment of corporeal and spiritual maintenance and review. It is a reminder that I am human and fallible; that I alone cannot solve antiBlackness; the poverty of my family; the malice that drips in studied succession from the lips of those who take the podium at the White House; on the House and Senate floor; in law enforcement and promulgation bodies across the world. I am not capable, nor am I indictable. This is way of people, today. This is the ordered structure and method of living and dying, of dealing life and death, of imputing and supplying the of status servant and master (repeated in employee-employer relationships and class, caste and racial structures). I am reminded that this order, this social order, is a definitely human bloodsport that requires a communal suspension of disbelief, good sense and morality; so that things might be ordered, things might be predictable, some people might be thingified and others might be (demi) deified.

It also reminds me to continue to the serious work of practicing abolition—in terms of the afterlives slavery and how these logics govern the ways in which I interact with self, others, children, my partner, the state and notions of violence, safety and defense—and decoupling my sense of self from worth and (racial) capitalisms. That is not simply to say I’m doing the constant work of distancing myself from the logics of the plantation and the capitalist notion of valuing myself according to whatever metrics of the modern auction block prevail; but instead to say I’m doing something quite different. I’m attempting to imagine myself outside of valuation. I’m attempting to imagine myself outside of—and not in conversation with—servitude, service or subordination. I’ve come to understand that the very foundation of both slavery and capitalism are the (de)valuations of the body as either surplus/excess, just enough/average or debt/gluttony. I have also come to know that these foundational logics of statecraft and publics-making have been operationalize to both tie us to work and production as signifiers of value; and as life as a quest to produce and be valued.

My dear friend and mentor, Saru Matambanadzo, a leading legal scholar in the field of employment and labor law, concerning with the critical interplay between race, class, (a)gender(s) and power recently engaged me on this line of thinking, when presenting her paper at the ClassCrits: Racial Capitalism symposium she hosted at Tulane a week or so ago. A longtime proponent of workplace and educational accommodations—which rests on the notion that everyone should have access to work—she questions, in her forthcoming work, whether paid work is the answer? She questions our corporeal and psychosocial ties to work as valuation and work as the presumptive tether that gives access to life, livelihood, dignity, health and the like. I offer the intervention that people—especially Black people—should not have to work at all. That we have progressed technologically to the point where work should be obsolete and further, that work itself—let us be reminded of enslavement, jim crow, and the surplus work Black people still must do in order to be seen as deserving of civilized contempt and servitude—has never been the pathway to personhood or equity or external dignity for Black folks. That is another conversation for another day, perhaps, my next article?

In any case, I wonder what portals might open when we consider Death as important—or even more important and certain—than Life? How might we reorient ourselves in the present? How might we have in the past? How might this reconstitute the future? What if the desire for death becomes a call, not for an examination of the declarant, but of the world and reality and logics we have inherited and continue to maintain? What if the desire for death is an indictment of life; and not evidence of the debasement of the one who dare bear good witness? And perhaps, what might come if our response was not to remind one of the work they could, should or must do? If the duty to live was not predicated on work, production, labor, debt? If there was no duty to live? What kind of people might we be, if we came to understand life not merely as a gift from the Divine, but as a gift from strangers and loved ones alike? Think with me.

you over here cookin’!!!